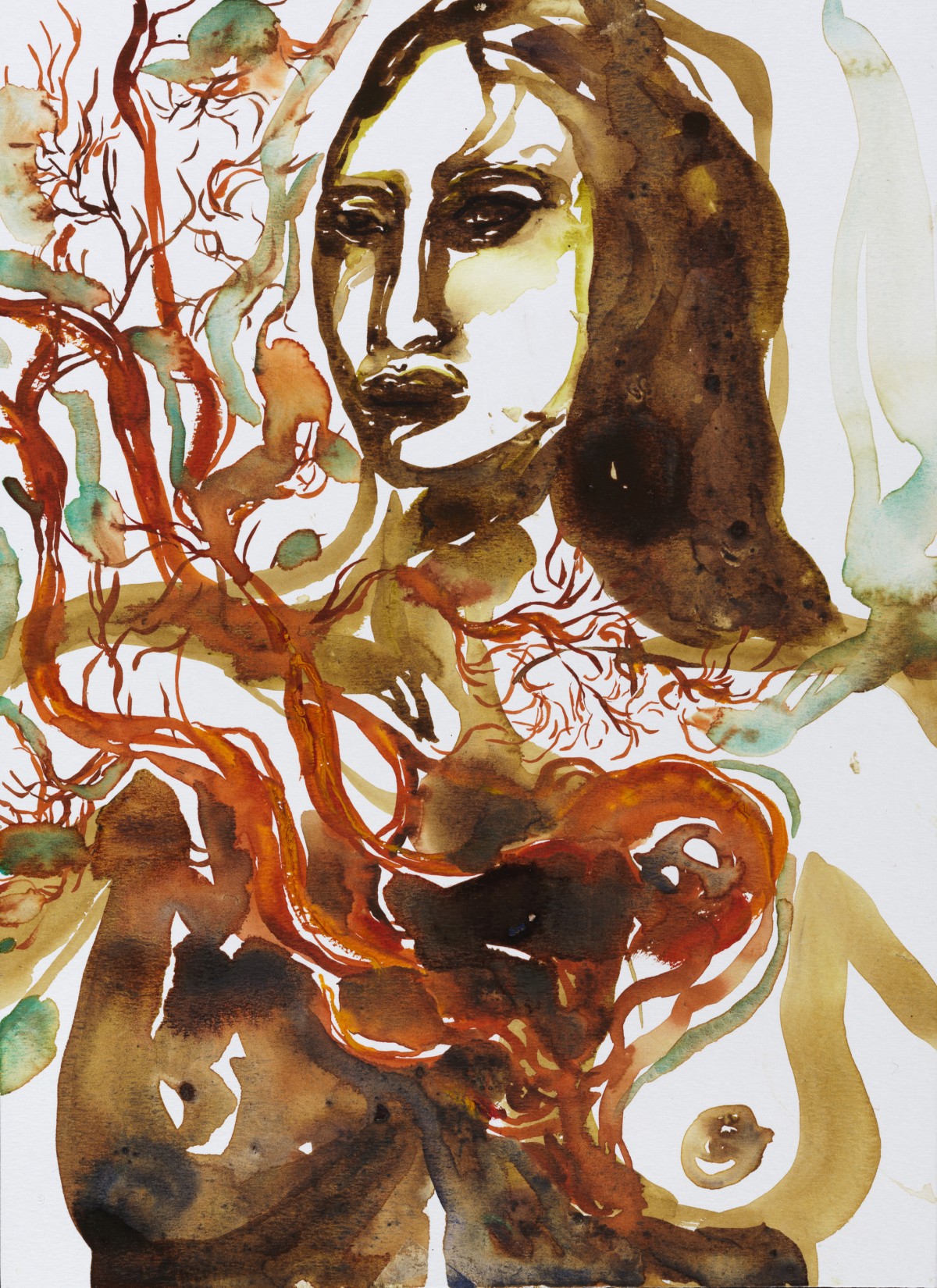

What if it all disappears? The protection, the top layer, the exterior? What if we take off our clothes, not necessarily to get in the shower but to expose ourselves to everyone's gaze. Let's say our house, which we regard as a safe cocoon with its closed doors, is made transparent by us – the windows too – so that everything is wide open and visible. And say our skin no longer separates our innermost being from the outside world. Say that everything can penetrate skin (to paraphrase the wonderful debut film by Esther Rots Can Go Through Skin, from 2009). That all thoughts, emotions, organs and blood currents become visible and, conversely, that everything enters unfiltered as well. What do you then see? What happens?

Women appear in the frequently monumental watercolors that Aline Thomassen (Maastricht, 1964) has been producing since the late 1990s. They are almost always naked, and their hips are wide; sometimes they're holding a (large) child in their arms, or a lot of children hover around them. Like a fairytale, a wish, a glimpse into the future perhaps: this many children are possible. At times the bodies are covered with fine calligraphic writing or strange suction cups that grow from a back into the space and seem to sway in the wind. Thomassen's women have a mysterious quality, despite their large build.

The women don't pose or present themselves at their best; nor do they give us a friendly smile. No, they look at me and the visitor intensely. Sometimes with eyes that each have a different meaning: one dark and probing, the other light and inviting. When seated, their broad thighs are splayed apart. Folds in the abdomen, sagging breasts, a vagina about to burst open – everything is on view. An organ to be clutched like a gift, in a proud and lively way.

Aline Thomassen grew up in Maastricht and in Annecy, France. Now she lives in The Hague and partly in Morocco as well. Once she headed off to Morocco after graduating from the Koninklijke Academie voor Beeldende Kunsten in The Hague in 1994, with the somewhat general intention of drawing portraits of inhabitants along the entire Mediterranean coast, it was clear to her. She would not travel further. She would remain there. In her studio in The Hague she describes how, on the boat from Gibraltar to Tangier, she fell in love on seeing, from the sea, the contours of the hills and the minarettes. That love continues to this day.

"It certainly wasn't easy in the beginning," she says to me. "I found it really scary in Tangier. In the evening I didn't dare go out anymore, since I was being pursued out on the street, men hissing at me. And I was denied entry to the hammam. 'No foreigners here,' they shouted at me."

A helpful boy at her hotel suggested she go to Larache, a less touristy place than the metropolis of Tangier. At the time it was still a simple, small-scale harbor town. There she won the trust of the local population and came in touch with women. She asked if she could draw them. First one agreed to, then others followed. She bought a house. Learned to speak Arabic. Her children went to the Moroccan school there for a few years.

Of course, she says in her studio, there is often great inequality between men and women there. "I don't want to idealize anything. Throughout the country's entire society, there is great inequality and injustice."

It's easy to have an instant opinion about this, but Thomassen's work doesn't engage in judgments. "In the Netherlands," says Thomassen, "we're tied up in a neoliberal straitjacket. I feel that every day: the compulsion to be productive, efficient, rational. I'm fairly exuberant by nature. In my body emotions lie on the surface, and I find it difficult to hide them. In the Netherlands I'm called 'hysterical', but in Morocco I feel included. In sync. It's as if my temperament is absorbed into the environment there."

"In Morocco I'm allowed to talk about sadness, grieve for a loss, as I did long ago after losing a child. Grieving can never last too long in the Netherlands, and sadness can't be expressed too often. In Morocco suffering is part of life, just as death is part of life. In Morocco I have three children: two in this world, and one in the other world. That's how they gently put it. Here in the Netherlands, I'm the Aline who has just two children."

Her work gives the impression of association. Everything seems to have been set down on the paper in quick, expressive strokes. But nothing could be further from the truth. The large watercolors on top-quality Arches paper, with its 100% cotton fiber, begin with a background of color. In order to choose that color Thomassen first needs to 'descend' into herself, as she puts it. She must delve down to the unspeakable feeling that she wants to portray. Initially she chooses the color that best responds to the emotion that she has. This is an intuitive process. It could be olive green, but also rust brown, nocturnal blue or yellow. Every color has a meaning. Some colors tend have a sinister quality, and others spread light.

After this she draws, with red or black brushstrokes, the contours of the figure that she wants to paint. If something goes wrong with the watercolor, she has no way of painting this over, as is the case with acrylic or oil paint. Each version of a work on paper – almost always untitled – consists of a number of 'shadow versions', which are destroyed. Only after she has established those contours – those of the gaze and the expression, and then a lock of hair, a waist or a pair of hands simply emerging from a midriff – can she continue working. Then the body is marked with enigmatic forms: as though a conversation arises between the woman and the artist. Where do you want to go, whispers the artist to the depicted figure. What drives you?

At times the forms give the impression of pain or injury: spots, stains, pools of fluid whirl across the bodies. It's as if each body has been wounded and is leaking. Nonetheless, the women are still standing proudly – good and evil, beauty and ugliness, they carry it all with them.

Aline Thomassen's women are the result of a violation that has been overcome by a love of life. The women are invincible – which is not the same as being unaffected. Everyone is affected by life. Everyone's skin is a reflection of the soul. Each mark on that skin has meaning. And every sorrow endured opens a window – to more light. This is what the women depicted by Aline Thomassen project with enormous power: ultimately, when you have a good heart, nothing can happen to you.

Translation: Beth O'Brien