Press release Hester Oerlemans | Hurry Slowly

They look festive, the large canvases hanging across the streets in Aleppo. However, the canopies, sheets and curtains serve a macabre purpose. They’re meant to block the view of snipers hiding in the abandoned houses of the largely destroyed city. Thanks to these gently swaying textiles, residents can cross the street quickly without walking into sight. What looks like decoration, like a cheerful splash of color in a battleground as grey as dust, offers meagre protection from ruthless violence. The wry beauty of the canvases is captured in a photo essay in Time. [1]

It is these photographs that inspired Hester Oerlemans to create a six-part series of paintings collectively titled Sniper Curtains (2019-2021). The representation is reduced to a few lines indicating the outline and pleats of the curtains, sometimes in black, but mostly in bright shades of blue, yellow, green, or orange. The result is a simple yet strong image as forceful as an icon. The lines are cartoonesque: flowing, efficient, expressive, and effective. The fact that the curtain nearly covers the painting creates an almost paradoxical feel. A curtain, normally used to keep something out of sight, becomes a painting that wants to give insight, something we have never seen before – the unexpected closeness of festive decorations and terror.

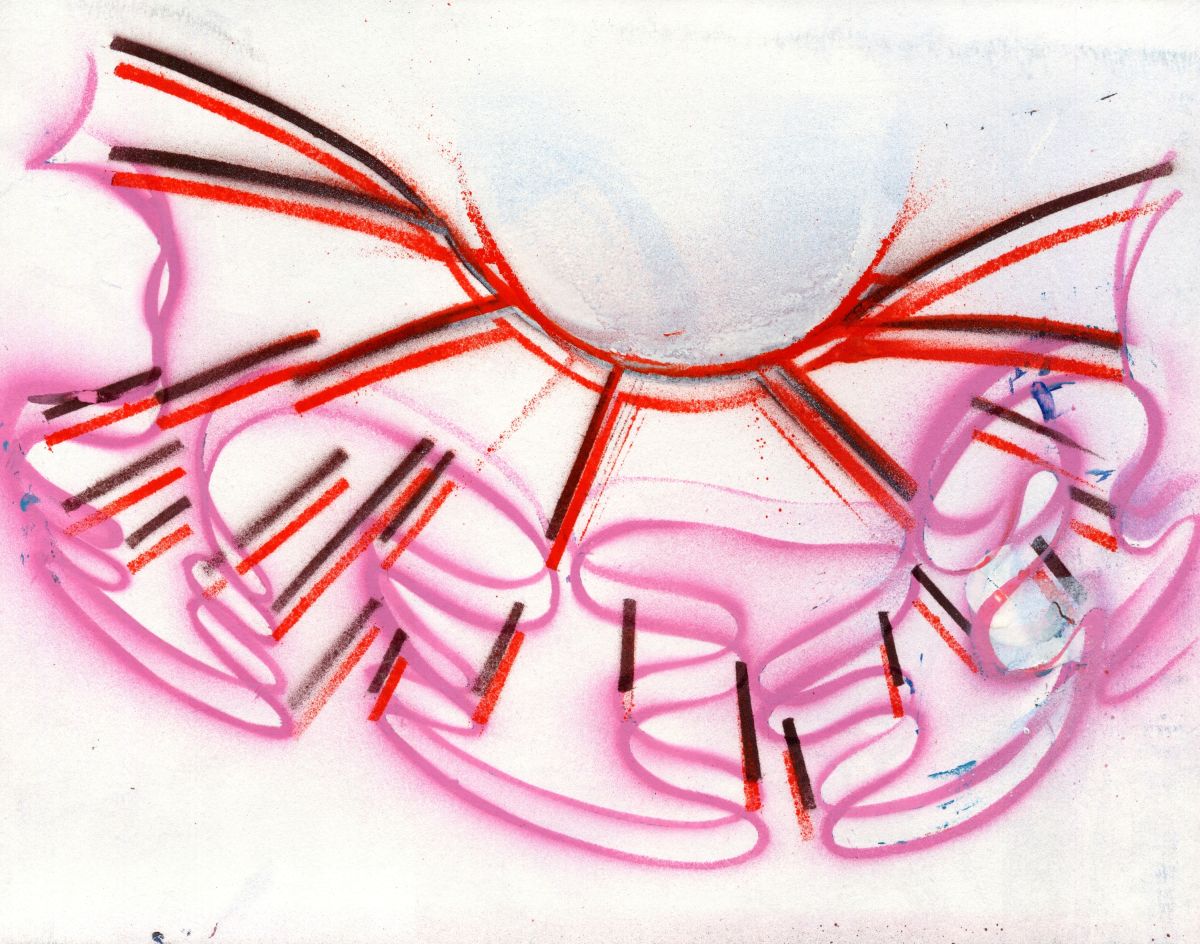

Oerlemans doesn’t use paintbrushes but stencils and sprays cans. The templates, which she makes herself, are of paper in which she cuts out lines to depict the image. To prevent the delicate templates from falling apart, she lines them with a gauze fabric (which is still recognizable in some of the spray-painted parts). Oerlemans’ self-conceived and perhaps somewhat laborious way of painting does give her work a strongly graphical character that certainly draws your attention. Her paintworks hint at graffiti.

The Sniper Curtains drawings were also made with a stencil, which was temporarily stuck to the paper for convenience. On some, the traces of glue are still visible. In some drawings, pieces of gauze or perforated sheet iron have been used as templates. The drawings look direct, unadorned, and fresh; they show undisguised traces of their creation. The key to their energetic effectiveness is the linework, in particular that inimitable balance between precision and nonchalance, between spontaneity and perfection. It’s this hard-to-control quality that Oerlemans attempts to translate into larger-scale paintings.

Before studying at art school, Oerlemans took a graphics course, so printing techniques are familiar to her. Using screen printing, she has created numerous posters for artists’ initiatives such as her self-founded Oceaan in Arnhem, which later followed up with Ozean in her current hometown of Berlin. The stencil is the servant of repetition, but the repeated use of the same templates does not lead to monotonous results. Each of Oerlemans’ drawings and paintings is unique, just a tad different each time. Although the different versions of the Sniper Curtains are equal in nature, some development can still be noticed. Working in the studio, the artist gradually tends towards further reduction, towards less detail and greater clarity. “By working in series,” she says, “you notice that as a painter, you can make do with less and less.” [2] Not coincidentally, Henri Matisse is one of her heroes.

The images that fascinate Oerlemans include not only the curtains of Aleppo but also the daily news photos of migrants, refugees and so-called status holders in asylum seekers’ centres, a hot topic in Dutch and international politics. Using stencils, Oerlemans made drawings and paintings of sports halls full of empty cots. Next to the beds, she painted the names of those spending the night at these temporary shelters – Ibtisam, Raafat, Zahed Hehly, Arabic names that a Dutch tongue could easily struggle with. In this way, Oerlemans reunites the refugees with their individual identity that is too often taken from them by the system (What’s Your Name, 2017). The performances make politics personal and the personal political, bringing abstract developments on the world stage down to human scale. The refugee theme is also central to some designs for a monument in the shape of a giant flip flop, a plan that has so far not been implemented (Refugee Monument, 2017).

In a selection of recent paintings, the artist has reversed her tried-and-tested method. Whereas she used to seek the essence of an image by translating it into a few racy lines with the help of a stencil, she now sticks laser prints of an enlarged photograph firmly onto the canvas and then paints away all excess image information. The method creates opportunities to tweak an image for longer, to complete it with the utmost nuance, something that is more difficult with stencil painting. The result is an intriguing confluence of photographic and painterly image information.

The tension between anonymity and visibility is also a leitmotif in this group of works. Justice (2021) shows someone shielding their face with a binder to avoid being recognized. In On Hold (2022), we see a woman hiding under the mattress she carries on her head. Kreuzberg (2022) features an abandoned shopping trolley with a rolled-up Persian carpet, based on a snapshot the artist took in this Berlin immigrant neighbourhood. It could be an unattended shopping trolley, an impromptu move, an unexpected eviction – the true story behind the enigmatic show is never made explicit.

Opposites collide: the domestic and the nomadic, the Western and the Eastern, the familiar and the strange. In her own words, the artist is fascinated by the sudden proximity of that which comes from afar. Oerlemans: “I initially feel triggered by the colours and exotic patterns in the photographs, but also by the underlying issue of global migration, why people leave their home and all they’ve ever known.” [3] Complex questions without unambiguous answers, an asylum seekers’ centre is both a place of stagnation and a refuge of hope.

The paintings anticipate not so much the misery of migrants but rather the preconceived perceptions of the public. On the Run II (2015), for example, which depicts an African with a bed on his head, is often interpreted as a portrait of a refugee, but what refugee takes his cot with him on the run? The cheap white plastic garden chairs you find all over the world are generally considered to be disgusting but in Oerlemans’ intensely melancholic painting No Title (2022), they appear as the last interpreters of human dignity. Hurry slowly, the title of the exhibition, can be understood as an invitation to suspend overly premature conclusions, even just for a while.

The fact that property, housing, and status are important indicators of social identity applies not only to today’s poor asylum seeker but also to wealthy people throughout history. In 17th-century portraits of Dutch merchants and regents, the white ruff symbolises the wearer’s social position. The bigger the ruff, the higher the owner’s standing. What started out as an upstanding ruff to protect the outer garment (a fashion trend originally from Spain) soon developed into the so-called millstone collar: always snow-white, wide, and symmetrically pleated and starched. The precious, fine-grained linen seemed almost translucent, as can be seen in paintings by Rembrandt and Frans Hals. Oerlemans has made dozens of drawings (and a painting) of such ruffs, in which she meticulously reconstructs various types of pleats. However, the wearer of the coveted garment remains out of the picture, rendering the exquisite sophistication of the display of power hollow and meaningless.

Clear, uncluttered images of a murky, complex reality is how one could characterize Oerlemans’ paintings. Her images are catchy like a cartoon and, like the visual joke, rely on ambivalence and ambiguity. Perhaps this is best illustrated by one of her sculptures, Seat (2017), consisting of the seat of a Marko brand plastic chair. As the back and seat are folded together, a striking resemblance is created to Donald Duck’s beak. In Disney’s standard repertoire, that beak is the most difficult part of the well-known cartoon character to draw. Oerlemans’ wall sculpture lets the visual motif spring from unexpected sources with natural grace.

The chair as beak is essentially no different from the curtain as a makeshift shield. In simple compositions, Oerlemans depicts the fragility and strength of an existence cast adrift by migration and globalisation.

Text: Dominic van den Boogerd

[1] Rania Abouzeid, ‘The Veils of Aleppo: Photographs by Franco Pagetti’, Time, April 8, 2013

[2] De kunstenaar in gesprek met de auteur, Amsterdam, December 12, 2022

[3] idem